You feel feverish. Often taken as the first sign of an infection, you feel exhausted, and hot and clammy. The usual response is to go to bed, and take aspirin, paracetamol or ibuprofen- to lower the body temperature.

It has long been acknowledged that such drugs could, in theory, be counter-productive, they do after all, interfere with the body’s natural response to infection. These concerns have been largely set aside, however, for a variety of reasons, the need to relieve discomfort, fears about febrile convulsions in young children, simple habit, and some might add the psychological urge to do something rather than nothing.

Febrile convulsions, whilst frightening for parents, almost never cause lasting harm. In any case, they seem to be caused by a rapid climb in temperature, rather than a raised temperature as such. One paediatrician said: “I consider the thermometer a common source of undue parental anxiety. Physicians frequently are asked to ‘treat’ a fever, but this pressure to ‘do something’ should be tempered by the realization that, in most cases, fever is merely the body’s defence against a self-limited disease.”

The upshot is that the drugs, used as anti-pyretics, are routinely used in vast quantities for any feverish illness, from the sickest of patients in intensive care, to people using over-the-counter cold remedies at home. Standard medical advice for flu, for example, is to rest and dose up on paracetamol..

New findings are starting to support a traditional view of fever, that it is a key part of the body’s disease fighting strategy. Recent evidence is emerging from three areas; firstly, new insights into how the immune system battles infection, secondly, how bacteria respond to changes in temperature, and thirdly, continuing studies of critically ill patients. Additionally, the idea that artificially lowering a child’s temperature with antipyretics can prevent febrile convulsions is not consistent with new research.

It was the emergence of modern medical science in the mid-19th century that led to fever being seen as harmful. In the 1860’s, French physician Claude Bernard developed the concept of homeostasis, the property of a living organism that regulates its internal environment and tends to maintain a stable, constant condition, within a relatively narrow range. Deviation from this range was regarded as sub-optimal for health. As an easily understood example, generations of doctors were taught the concept using body temperature, and the mercury-filled clinical thermometer, newly available, could be used with impressive precision. Just as impressive to the patient was the way a doctor could lower their temperature using aspirin and later, paracetamol.

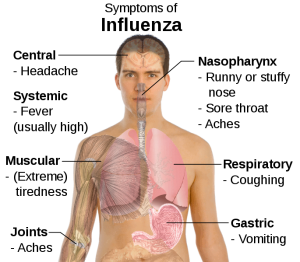

Fever arises when the immune system, sensing an infection, produces proteins known as pyrogens. These act on the hypothalamus to raise the body’s temperature from around 37oC , typically rising to 39oC or 40oC.

It seems that many of the body’s disease fighting mechanisms function more effectively in hotter conditions. For example, the well-known ability of the immune cells known as T-lymphocytes to home in infection sites, but also, intriguingly, fever may lie behind stories of so-called spontaneous remission of certain cancers, notably those of the skin, testes and kidney, as well as some forms of lymphoma and leukaemia. The accompanied rise in metabolic rate, which may be experienced as the discomfort of fever, appears to lie behind the recoveries.

Before notable strides were made in pharmacology, such diseases as syphilis, asthma and arthritis were treated by induced fevers. Episodes of acute diseases such as measles, with their fevers, have been noted to have a beneficial effect on other pre-existing diseases. In fact, it is a matter of record that Pasteur challenged the members of the French Academy of Medicine to inoculate a chicken with a fatal dose of anthrax. They could not do it because a chicken has a normal temperature of 41oC, which will not permit anthrax bacteria to live.

Among other reasons that some give in support of the position that fevers serve a useful purpose are these: Fevers cause the body to produce a recently discovered substance, inferon, helping it to combat viruses. Fevers also stimulate the production of enzymes and white corpuscles.

This is a subject where evidence tends to be anecdotal, rather than intensively researched, say by randomised controlled trials. There is however, considerable evidence that antipyretics hinder, rather than help the body’s response to the common cold, chicken pox and malaria. The practical experience of infectious disease consultants suggests a better outcome for patients admitted with fever as compared to those without.

A relevant randomised trial carried out by researchers at the University of Miami in 2005, studied 82 critically ill patients who did not have head injuries or other problems that make a high temperature risky. Patients were randomised to get either the standard treatment of anti-pyretics if their temperature rose above 38.5oC, or those only given the drugs if their temperature reached 40oC. As the trial progressed, there were seven deaths in people receiving the standard treatment, compared with one in those whose fever was allowed to run its course. The trial was halted when it became apparent it could be unethical to continue with the standard treatment!

The reality is, for many people with fever, treatment we don’t know for certain is appropriate, necessary, or downright harmful has become the norm. Always remember prolonged use of anti-pyretics to reduce fever or seemingly minor influenza-like symptoms can mask more serious conditions. If in doubt, always consult a health-care professional.

References: New Scientist, 31 July 2010, p42

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/Can a fever cure cancer?, 21 September 2010, p 40 With thanks

See also: http://www.babble.com/don’t fear the fever

http://www.sfgate.com/Why is there an epidemic of fever phobia?