What is behind the history of dragons? Ancient peoples from all over the world spoke about unusual, reptile-like creatures (large and small) that once roamed the earth. Europeans called them “dragons,” originally from the Greek drakon apparently from drak-, strong aorist stem of derkesthai.” Perhaps the literal sense is “the one with (deadly) sight.” Scientists agree that legends are often based on facts, not just imagination. Dragon pictures are found in Africa, India, Europe, the Middle East, the Orient and every other part of the world. Dragon history is universal throughout the world’s ancient cultures. Where did this global concept originate? How did societies throughout the world describe, record, draw, etch, sew and carve such creatures in consistently similar ways?

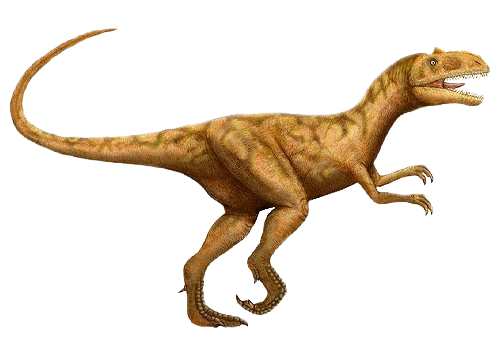

Dinosaur-like animals have been drawn and written about since the beginning of recorded history. People forgot about the history of dragons, and centuries later in 1822 the first dinosaur bone was discovered. It was thought to have come from a giant iguana, hence the term ‘Iguanodon’.

Many evolutionists believe that dinosaurs became extinct millions of years before man walked the planet, but think about the world’s legends about dragons. Dragons are drawn on cave walls; written about in ancient literature, and part of every culture of the world, causing many to believe that what these people saw were actually dinosaurs. There are dinosaur fossils, which have been discovered along with human footprints, adding to the picture. Furthermore, there are contemporary, unusual dragon or sea monster sightings.

The dinosaurs thrived during a period characterised by a climate best described as a ‘greenhouse’ or tropical rainforest. Reptiles are cold-blooded creatures and need warm temperatures. Unlike mammals they will continue to grow in size given optimum conditions. Research is indicating however, some dinosaur species at least, were not so limited.

People seldom realize that paleontology (the study of past geological ages based primarily on the study of fossils) is a relatively new science. In fact, the concept of dinosaurs (giant lizards) only surfaced in its present form less than 180 years ago. Prior to that, anyone who found a large fossilized bone assumed it came from an elephant, dragon or giant. There wasn’t any notion of “science” attached to these finds.

In 1824 the bones of several kinds of fossilized reptiles were unearthed in England. British paleontologist Richard Owen called these animals Dinosauria, from the two Greek words deinos and sauros, meaning “terrible lizard.” The name remains in common use to this day, although while dinosaurs are reptiles, they are not lizards.

Since 1824, dinosaur fossils have been found on every continent. The fossil record, left in layers of sedimentary, or water-laid, rock, indicates that there was an extraordinary abundance and variety of dinosaur types at a time in earth’s history called the Age of Dinosaurs. Some made their home on land, while others lived in swamps. Some lived in water, much like the present-day hippopotamus.

Dragon History – A Summation of the Evidence

Where are all these accounts of dragon history? Starting with the Bible, a search for the word “dragon” in the King James Version of the Bible produces 34 separate matches across 10 different books. The word “dragon” (Hebrew: tannin) is used throughout the Old Testament, and most directly translates as “sea or land monsters.” In the Book of Job, the author describes the great creatures, Behemoth (Job 40) and Leviathan (Job 41). Although the latest Bible translations use the words elephant, hippopotamus or crocodile instead of Behemoth and Leviathan, the original Hebrew and the context of the descriptions allow for alternatives.

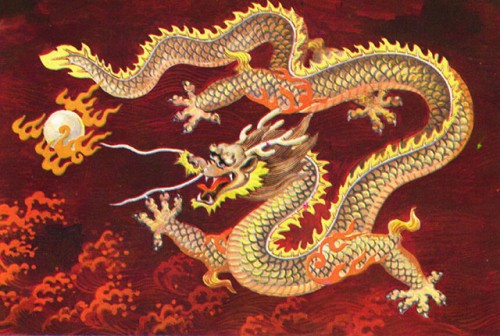

Of course, dragon history is by no means limited to the Bible. Literature from China, Europe, the Middle East, and ancient Latin America share similar accounts of “dragons” and other beasts. Some cultures revered these creatures. For instance, records of Marco Polo in China show that the royal house kept dragons for ceremonies and dragons were hunted for meat and medicine in the Province of Karazan. Records of the Greek historian Herodotus and the Jewish historian Josephus describe flying reptiles in ancient Egypt and Arabia. In other cultures, it was a great honour to kill these creatures. There are numerous records of warriors killing great beasts in order to establish credibility in a village. Gilgamesh, Fafnir, Beowulf and other famous legends, including the mythology of Egypt, Greece and Rome, include descriptions of dragons and other dinosaur-like creatures.

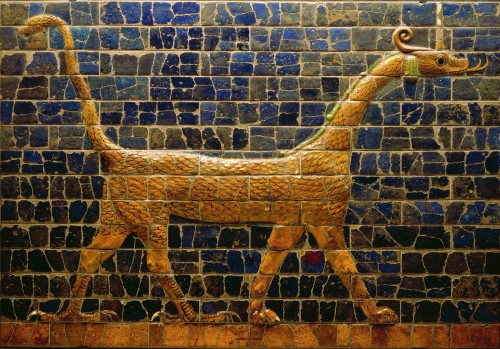

Dragon history is revealed on numerous objects of ancient art throughout the world. Dinosaur-like creatures are featured on Babylonian landmarks (the sirrush), Roman mosaics, Asian pottery and royal robes, Egyptian burial shrouds and government seals, Peruvian burial stones and tapestries, Mayan sculptures, Aboriginal and Native American petroglyphs (carved rock drawings), and many other pieces of ceremonial art throughout ancient cultures. Incidentally, the Babylonian sirrush may represent sightings of sea serpents, with lower limbs conjectured.

Almost all our early ancestors believed the earth was inhabited, especially in unknown regions, by dragons. Where did they get such an idea? Did it stem from a universal human imagination? An inherited need or instinct? An inherited subconscious memory of dinosaurs? The possibility is here considered that dragons are the reflection, perhaps embellished through re-telling, but mostly historical, of actual physical encounters of human beings with dinosaurs.

The book Vanished World: Dinosaurs of Western Canada states that “all of the eleven major kinds of dinosaurs . . . ceased to exist in the western interior at about the same time.” This, and the fact that human bones have not been found with dinosaur bones, is why most scientists conclude that the Age of Dinosaurs ended before humans came on the scene.

However, it should be noted that there are some who say that dinosaur bones and human bones are not found together because dinosaurs did not live in areas of human habitation. Such differing views demonstrate that the fossil record does not yield its secrets so easily and that no one on earth today really knows all the answers.

Has it really been proven that dinosaurs became extinct prior to the advent of man? There is much to indicate that dinosaurs and humankind existed on earth contemporaneously, and that human beings did encounter the sometimes huge and fearsome creatures. The memories of these encounters were so vivid that they were passed down in a multitude of cultures as legends, painted on cave walls, represented in pottery, and written in literature.

The Riddle of the Dinosaur commented: “Authors with varying competence have suggested that dinosaurs disappeared because the climate deteriorated . . . or that the diet did. . . . Other writers have put the blame on disease, parasites, . . . changes in the pressure or composition of the atmosphere, poison gases, volcanic dust, excessive oxygen from plants, meteorites, comets, gene pool drainage by little mammalian egg-eaters, . . . cosmic radiation, shift of Earth’s rotational poles, floods, continental drift, . . . drainage of swamp and lake environments, sunspots.” It is apparent from such speculations that scientists are not able, with any certainty, to answer the question: What happened to the dinosaurs?

Etymology of “dragon”

The word “dragon,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary (1966), is derived from the Old French, which in turn was derived from the Latin dracon (serpent), which in turn was derived from the Greek spakov (serpent), from the Greek aorist verb, spakelv (to see clearly). It is related to many other ancient words related to sight, such as Sanskrit darc (see), Avestic darstis (sight), Old Irish derc (eye), Old English torht, Old Saxon torht and Old High German zoraht, all meaning clear, or bright. The roots of the word can be traced, then, back to most early Indo-european tongues. This may indicate that it is possible the immediate ancestor of the word was a part of the original hypothetical Indo-european tongue.

The Oxford English Dictionary points out that spakelv is derived from the Greek stem spak meaning strong. The connection with dragons is obvious. According to the OED, the word was first used in English about 1220 A.D. It was used in English versions of the Bible from 1340 on.

The book, The Greatest Monsters in the World, (1986), contains a chapter called “Dragons Everywhere.” This title is accurate, because ancient belief in dragons appears to have been nearly universal, as far as we can determine from prehistoric art, legend, and the world’s most ancient writings.

In art, dragons are a motif used in ancient pottery. The motif appears as bowl decorations in China as late as 202 A.D. The Bali portray a dragon in their animal mask of Barong, a good spirit that is central in their ritual dramatic presentations.

Perhaps the earliest evidence, however, is found in a prehistoric cave at La Baume, Latrone, France, discovered in 1940 by Siegfried Giedion. Peter Costello writes, “dominating the whole scene is a serpent over three metres in length.” As Costello notes, this picture of a dragon-like creature “appeared at the very dawn of art,” whatever its exact date ( In Search of Lake Monsters ).

At Lydney Park on the banks of Severn in Gloucestershire, England, a mosaic floor of Romano-celtic origin has been excavated. It appears to be a temple associated with the river cult of Nodens, “the cloud maker.” Prominent in the mosaic are sea monsters that may well be considered dragons.

Dragons in Ancient Literature

In literature, dragons are certainly a virtually universal ancient motif. Dragons are found in the early literature of the English, Irish, Danish, Norse, Scandinavians, Germans, Greeks, Romans, Egyptians and Babylonians. Among the American Indians, legends of dragons flourished among the Crees, Algonquins, Onondagas, Ojibways, Hurons, Chinooks, Shoshones, and Alaskan Eskimos.

One of the most famous Danish dragon tales is from “Sigurd of the Volsungs” and concerns “The Slaying of Fafnir.” Sigurd, the hero of the epic, is afraid of Fafnir the dragon because his tracks seem great. This surely would have been true of the large dinosaurs, whether the footprints themselves or the sound of their approach were being considered. Sigurd hides in a pit, and when the dragon crawls to the water, he strikes up into its heart. Again, if a man were to slay a large dinosaur, this would be an intelligent way to do it, for one would be out of the way of the creature’s powerful tail and sharp, meat-rending teeth. Probably the head, neck and heart were the only truly vulnerable areas on the huge body. Sigurd is afraid he will drown in the dragon’s blood, which may be another indication as to the size of the creature. If the dragon had fallen over the mouth of the pit, Sigurd’s drowning in its blood would have been a distinct possibility.

As the dragon approaches, it blows poison before it. The dragon talks to Sigurd. In the talking we undoubtedly have some embellishment, but this is not surprising in an early folk tale that was passed down for uncounted generations. Sigurd’s friend, Regin, cuts out the dragon’s heart, and asks Sigurd to roast it and serve it to him. When Regin touches the dragon’s blood to his tongue, he understands the speech of birds. Here again we probably have an embellishment, perhaps associating dragons in a symbolic way with wisdom, a frequent association in early literature.

Both the dragon in this early Danish epic and the dragon in the Old English epic, Beowulf, guard a treasure. We can only speculate as to the origin of this idea. It’s possible that a dinosaur did in fact make off with some loot, or it’s possible that the abode of dinosaurs was so unapproachable that ancient peoples imagined their dens to be loaded with treasures. Did the two dragons come from the same early legend? We do not know.

The unnamed dragon in Beowulf also vomits flames. Could the idea really recall the stinging or burning sensation of the saliva or venom? It is fifty feet long, as measured after its death. As with Fafnir, “earth dwellers much dread him.” He is a night creature, associated with evil, and described as “smooth” and “hateful.”

Dragons in Legend and Folklore

Greek heroes who are supposed to have slain dragons include Hercules, Apollo, and Perseus. Indeed, one authority states: “The dragons of legend are strangely like actual creatures that have lived in the past. They are much like the great reptiles [dinosaurs], which inhabited the earth long before man is supposed to have appeared on earth..every country had them in its mythology.” (Knox Wilson, “Dragon”,The World Book Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, 1973, p. 265.) In Norse mythology, a Great Ash Tree, Yggdrasil, which was thought to support the whole universe, had three immense roots. One extended into the region of death. Niflheim and the dragon Nidhogg perpetually gnawed at the root of the tree. This precarious situation, which seems to place the whole universe at Nidhogg’s mercy, perhaps shows the conscious or subconscious deeply rooted fear of dinosaurs, ‘terrible lizards’. If the fearsome creatures were threatening the ancestors of the Norse peoples, one can easily see how such a myth could have developed.

The Egyptians wrote of the dragon Apophis, enemy of the sun god Re. Recent studies of ancient Egyptian (and other) artefacts have revealed that they conceivably observed at least several pterosaur species now known from the fossil record because of the morphological characteristics that were depicted. The Babylonians recorded their belief in the monster Tiamat. The Norse people wrote of Lindwurm, guardian of the treasure of Rheingold, who was killed by the hero Siegfried. The Chinese wrote of dragons in their ancient book, I Ching, associating the creatures with power, fertility, and well-being. They also used dragons in early art, ancient pottery, folk pageantry and dances as a motif. The Aztecs’ plumed serpent may have represented a hybrid in their thought between a dragon and another creature. The pottery of ancient Nazca culture of Peru shows a cannibal monster much like a dragon.

In British Columbia, Lake Sashwap is believed to be home to the dragon Ta Zam-a, and Lake Cowichan to Tshingquaw. In Ontario, Lake Meminisha is the reputed home of a fish-like serpent feared by the Cree Indians. Angoub is the legendary Huron dragon, Hiachuckaluck, believed in by the Chinooks of British Columbia. Lake Chelan, Washington state, home to Ogopogo, a monstrous reptile.

Dragons are so widely accepted a part of Irish folklore that Robert Lloyd Praeger, naturalist, says they are “an accepted part of Irish zoology.” Dr. P.W. Joyce, historian, in his book The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, says, “legends of aquatic monsters are very ancient among the Irish people” and shows that many Irish place names resulted from a belief in these dragons.

Dragon Interpretations

Many theories have been set forth proposing to explain the virtually universal belief in dragons among ancient peoples. Some have seen dragons as a product of the human imagination, resulting from fear of the unknown. It has been pointed out that as late as 1600 A.D., maps were decorated about the borders of unknown regions with drawings of dragon-like monsters. Yet it is hard to imagine how such widely separated people groups all imagined virtually the same thing, if that imagined entity had no basis in reality or in their experience.

Sometimes you read that people had a universal need to believe in these things, that the human ‘subconscious’ understood at some deep level the same set of symbols, perhaps gained through their common (supposed) evolutionary ancestry. The most frequent modern interpretation given to myths and archetypes is that they are subconsciously symbolic. One wonders, however, why it is only humankind that has left this constant, ancient record of dealings with dragons, and how such a memory could have lived through millions of years of evolution and changes into entirely different kinds of animals.

For these reasons, even many secular authors have come almost, but not quite, to the conclusion that early people encountered dinosaurs, and passed down the memory of these encounters in tales of dragons. Peter Costello, author of ‘In Search of Lake Monsters, wrote, “…as we go through the early accounts of Irish lake monsters we shall find that there is often only a superficial covering of fancy…real animals are clearly behind some of the stories. For example, the plesiosaur theory,” he writes, “which appeared early on, still has many supporters….but again the difficulties, whether it could have survived for sixty million years undetected…are very great.”

Daniel Cohen, author of ‘The Greatest Monsters in the World’, also says that there is a “sensational possibility” that the dragon legend originated with the dinosaurs, observing that “no creatures that ever lived looked more like dragons than dinosaurs…there is a problem with this theory. The problem is time. As far as we know, all the dinosaurs died out over 70 million years ago. That long ago, there were no people on earth. So who could remember the dinosaurs?”

Cohen says that “some early discoverers of dinosaur bones called them ‘dragon bones’.” But apparently because the time and evolutionary development problems are so great in the minds of those who have accepted this model of origins, Cohen boldly asserts that “scientists today no longer identify dinosaurs with dragons.”

The obvious conclusion is that except for their devotion to evolutionary theory, identification of dinosaurs with dragons would be the logical interpretation of the evidence.

Only two years after the publication of ‘The Greatest Monsters in the World‘, however, Carl Sagan, a renowned popularizer of the atheistic evolutionary interpretation of science, published The Dragons of Eden, which in spite of the time and evolutionary development problems asks, “Could there have been man-like creatures who actually encountered Tyrannosaurus Rex?” Sagan asserts, “One way or another, there were dragons in Eden.” Outspokenly an evolutionist, Sagan’s book is subtitled, “Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence.” He does not, of course, view Eden in the classical Christian or Biblical sense of the word. By “Eden,” he appears to mean an emerging humanity’s dawning awareness of their own place in the cosmos.

In conclusion, it must be considered that early humanity did encounter dragons, or dinosaurs. This means that humanity did not evolve millions of years after the dinosaurs became extinct, but that the two co-existed. Each piece of evidence by itself may possibly be explained away, but the evolutionary model of history which separates humanity and dinosaurs by millions of years leaves too many unanswered questions. How could a people draw pictures of dinosaurs on ancient cave walls, if none were around to serve as models? How is it that so many ancient cultures wrote about dinosaurs (dragons), if they were unknown to early humanity? How do the early literary accounts of dragons end up being so realistic, down to the smallest details?

It is often said that if evidence can be adduced from a number of different disciplines, it is strong indication to the veracity of a hypothesis. Here is evidence from archaeology, prehistoric art, ancient literature, legend and mythology, and the Bible. This evidence leads to the conclusion that human beings did indeed encounter dinosaurs, and that they drew them, wrote of them and passed on tales of them to their children. Were the dragons of ancient art and literature in fact dinosaurs?