In the year 1876, medicine man Sitting Bull of the Lakota (one of the three main divisions of the Sioux) was a leader at the famous battle of the Little Bighorn River, in Montana. With 650 soldiers, Lieutenant Colonel “Long Hair” Custer thought he could easily defeat 1,000 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. This was a gross miscalculation. He was facing probably the largest group of Native American warriors ever assembled—about 3,000.

Custer split the Seventh Cavalry Regiment into three groups. Without waiting for support from the other two, his group attacked what he thought would be a vulnerable part of the Indian camp. Led by headmen Crazy Horse, Gall, and Sitting Bull, the Indians wiped out Custer and his unit of some 225 soldiers. It was a heady, if temporary victory for the Indian nations, and a bitter defeat for the U.S. Army. However, terrible revenge was only 14 years away… Eventually Sitting Bull surrendered, having been promised a pardon. Instead, he was confined for a time at Fort Randall, Dakota Territory. In his later years, he appeared in public in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West travelling show. The once illustrious leader had become a mere shadow of the influential medicine man he used to be.

In 1890, Sitting Bull (Lakota name, Tatanka Iyotake) was shot to death by Indian police officers who had been sent to arrest him. His killers were Sioux “Metal Breasts” (police-badge holders), Lieutenant Bull Head and Sergeant Red Tomahawk.

In that same year, Indian resistance to the white man’s dominance was finally broken at the massacre of Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. There, about 320 fleeing Sioux men, women, and children were killed by federal troops and their Hotchkiss rapid-fire cannons. The soldiers boasted that this was their vengeance for the slaughter of their comrades, Custer and his men, on the ridges overlooking the Little Bighorn River. In reality, it was the sad culmination of 200 years of sporadic wars and skirmishes between the invading American settlers and the besieged resident tribes.

To many Native Americans, their ancestral lands are sacred. As White Thunder said: “Our land here is the dearest thing on earth to us.” When making treaties and agreements, Indians often assumed that these were for the white man’s use of the land but not for outright possession or ownership of it. The Sioux Indian tribes lost valuable land in the Black Hills of Dakota in the 1870’s, when miners flooded in, looking for gold. In 1980 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the U.S. government to pay about $105 million in compensation to eight Sioux tribes. To date the tribes have refused to accept the payment, they want their sacred land, the Black Hills of South Dakota, to be returned.

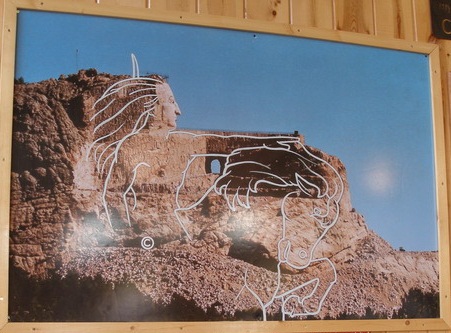

Many Sioux Indians are not pleased to see the faces of white presidents carved on Mount Rushmore, in the Black Hills. The completion of the Memorial to the four U.S. presidents prompted the Lakota elder Henry Standing Bear, in 1948, to commission Korczak Ziolkowski to create an image of an even bigger carving, Crazy Horse (Tashunkewitko), the Oglala Sioux war leader, to “show the white man that the red man has heroes, too.” But Native Americans have mixed feelings toward the massive carving and the huge sums of money the Ziolkowski family earns from it every year.

When Crazy Horse was bayoneted to death by another Lakota at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, on September 6, 1877, his legend lived on. For generations, his name has been a symbol to Lakota people of pride, courage and strength. Recognizing the power of Crazy Horse as an icon, Ziolkowski envisioned the monument as a metaphoric tribute to his spirit, and that of all Native Americans. His extended hand on the monument is to symbolize that statement.

Although the Lakota elder asked Korzcak Ziolkowski to carve a likeness of the slain warrior, it was a likeness based on oral history, because Crazy Horse always resisted being photographed and was deliberately buried where his grave would not be found. He reportedly said, “My lands are where my dead lie buried.”

Korczak Ziolkowski died in 1982, 16 years before the face of the carving was completed. For some Native Americans, the Crazy Horse Memorial is not only a place for employment, but a place that helps to balance hundreds of years of racism against their people.

Seth Big Crow feels less positive about the huge carving. His great-grandmother was Crazy Horse’s aunt. He feels resigned to the existence of the carving and rationalized that, in future years, it may be the American equivalent to the Easter Island monoliths.

“Maybe 300 or 400 years from now, everything will be gone, we’ll all be gone, and they’ll be the four faces in the Black Hills and the statue there symbolizing the Native Americans who were here at one time,” said Seth Big Crow.

But Seth Big Crow is concerned about the amount of money being generated by his ancestor’s name. Since Henry Standing Bear requested the mountain carving, the Ziolkowskis have built a complex of visitor centers and souvenir shops earning the family millions of dollars annually. Seth Big Crow wonders if Henry Standing Bear’s request was limited to the mountain carving alone.

“Or did it give them free hand to try to take over the name and make money off it as long as they’re alive and we’re alive? When you start making money rather than to try to complete the project, that’s when, to me, it’s going off in the wrong direction,” he said.

The complex is listed as part of Korczak Ziolkowski’s “expanded plan” for the site and, as noted on the memorial’s brochure, “Crazy Horse cannot be experienced by driving past on the highway.” The sculptor’s widow, Ruth, and seven of his children work at the Memorial. Daughter Anne Ziolkowski’s view on the controversy that the memorial has caused in Indian Country is blunt.

“Well, you’re not gonna’ please everybody,” said Ann Ziolkowski. “I don’t care what you do, you’re not gonna’ please everybody. If we offend people, we’re very sorry. But we’re doing what we were asked to do.”

The problem, according to Crazy Horse descendant Elaine Quiver, is that Henry Standing Bear had no right to petition Korczak Ziolkowski to create the mountain carving in the first place. She says Lakota culture dictates consensus from family members on such a decision. Ms. Quiver adds that no one bothered to ask the descendants of Crazy Horse if they approved of the project before the first sticks of dynamite were blown on land sacred to the Lakota on June 3, 1948.

“They don’t respect our culture because we didn’t give permission for someone to carve the sacred Black Hills where our burial grounds are,” said Elaine Quiver. “They were there for us to enjoy and they were there for us to pray. But it wasn’t meant to be carved into images, which is very wrong for all of us. The more I think about it, the more it’s a desecration of our Indian culture. Not just Crazy Horse, but all of us.”

Other traditional Lakota oppose the memorial. Lame Deer, a Lakota medicine man, said: “The whole idea of making a beautiful wild mountain into a statue.. is a pollution of the landscape. It is against the spirit of Crazy Horse.” Having the finished sculpture depict Crazy Horse pointing with his index finger has also been criticized. Native American cultures prohibit using the index finger to point at people or objects, as the people find it rude, or taboo. Some spokesmen compare the effect to a sculpture of George Washington with an upraised middle finger!

The Ziolkowskis have donated $500,000 to Native American students, an act Anna Ziolkowski says is part of her family’s show of respect for the culture. But Elaine Quiver and Seth Big Crow both question what’s become of the other millions of dollars collected at the Crazy Horse Memorial over the past 55 years. “One day when we go in front of the maker of all human beings, we’re going to have to explain our actions as to why, and money cannot be part of the explanation, because I don’t believe it’ll be recognized,” Elaine said.

Finally, a quote worth reflecting on,

“Before any final solution to American history can occur, a reconciliation must be effected between the spiritual owner of the land, the American Indians, and the political owner of the land, American Whites. Guilt and accusations cannot continue to revolve in a vacuum without some effort at reaching a solution… until we can once again produce people like Crazy Horse all the money and all the help in the world will not save us” (Vine Deloria, Jr).

Thanks to:

www.voice of America news.com 13th September 2003

www.en.wikipedia.org/Crazy_Horse_Memorial

Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto by Vine Deloria Jr. (1969)

Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown (1970)