In Britain and America, following recent Elections, fundamental questions are being raised about the nature of Democracy. In an era seemingly desperate for strong government, is a  system that creates mega-personalities, with policies taking a second place, “the best of all possible worlds?” Without straying into the party political arena, can any dispassionate observer see as ‘Democratic’, a system that functions by the consent of the majority, however slim that majority might be? Does history shed any light on how this came about?

system that creates mega-personalities, with policies taking a second place, “the best of all possible worlds?” Without straying into the party political arena, can any dispassionate observer see as ‘Democratic’, a system that functions by the consent of the majority, however slim that majority might be? Does history shed any light on how this came about?

“WE THE PEOPLE of the United States . . . do ordain and establish this Constitution.” These opening words of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution indicate the founding fathers intended the United States to be a Democracy. Of Greek origin, “Democracy” means “rule of the people,” or as Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, famously defined it at Gettysburg: “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Greece, itself recently experiencing a ‘Pandora’s box’ of economic and political woe, is known as the cradle of Democracy, as Democracy originated in its city-states, notably in Athens, as far back as the fifth century B.C.E. But Democracy then was not what we recognize today. For one thing, Greek citizens were more directly involved in the ruling process. Every male citizen belonged to an assembly that met throughout the year to discuss current problems. By a simple majority vote, the assembly determined the politics of the city-state.

Women, slaves, and resident aliens, however, were excluded from enjoying political rights. Thus, Athenian Democracy was an elitist form of Democracy for the privileged few. One half to four fifths of the population probably had no voice at all in political matters.

Nevertheless, this arrangement did promote freedom of speech, since voting citizens were granted the right to express their opinions before decisions were made. Political office was open to every male citizen. Controls were designed to prevent misuse of political power, or tyranny.

“The Athenians themselves were proud of their Democracy,” says historian D. B. Heater. “They believed it was a step nearer than the alternative monarchy or aristocracy to the full and perfect life.”

It is probably true to say that today pure Democracy no longer exists. Considering the sheer size of modern states and their millions of citizens, governing in this way would be technically impossible. Besides, how many citizens in the busy world of today would have the necessary time to devote themselves to hours of political debate?

Democracy has grown into a controversial adult, with many faces. As Time magazine explains: “It is impossible to divide the world into clear-cut democratic and non-democratic blocs. Within the so-called Democracies, there are gradations of individual freedom, pluralism and human rights, just as there are varying degrees of repression within dictatorships.” Yet, most people expect to find certain basic things under democratic governments, things like personal liberty, equality, respect for human rights, equitable taxation and justice by law.

This trend toward representative Democracy began in the Middle Ages. By the 17th and 18th centuries, earlier institutions, such as the Magna Charta and the Parliament in England, along with new political theories about the equality of men, natural rights, and sovereignty of the people, were taking on greater meaning. The revolutions in America and France in particular, caused many to question long held ideals.

By the second half of the 18th century, the term “Democracy” had come into general use, though sometimes viewed with scepticism. The New Encyclopædia Britannica says: “Even the authors of the United States Constitution in 1787 were uneasy about involving the people at large in the political process. One of the signatories, Elbridge Gerry, called democracy ‘the worst of all political evils.’” Notwithstanding, men like Englishman John Locke continued to argue that government rests on the consent of the people, whose natural rights should be treated by politians as sacrosanct..

Many Democracies are republics, that is to say governments having a chief of state other than a hereditary monarch, now usually a president. One of the earliest republics was ancient Rome, although again, Democracy was admittedly limited. Nevertheless, the partially Democratic republic lasted for over 400 years before giving way to the dictatorial Roman Empire.

Republics are presently the most common kind of government. Of the 219 governments and international organizations listed in a recent reference work, 127 are listed as republics, although not all are representative Democracies. In fact, the range of governmental forms of republics is wide.

Some republics are unitary systems, that is to say, controlled by a strong central government. Others are federal systems, meaning that there exists a division of control between two levels of government. As the name indicates, the United States of America has this latter type of system known as Federalism. The national government cares for interests of the nation as a whole, while state governments deal with local needs. An advantage of this arrangement should be greater flexibility, however it can lead to legislative anomalies, in Britain we sometimes call this a ‘postcode lottery’. Is there always a good distinction between national and local government, or does increasing bureaucracy lead to a wasteful inefficiency?

Some republics hold free elections. Their citizens may be offered a plurality of political parties and candidates from which to choose, this seems obvious, but the one party state is hardly unknown in modern times. Other republics consider free elections unnecessary, arguing that the Democratic will of the people can be carried out by other means, such as by promoting the collective ownership of the means of production. Ancient Greece serves as a precedent, since free elections were unknown there also. Administrators were chosen by lot and generally permitted to serve for only one or two one-year terms. Aristotle was against elections, saying that they introduced the aristocratic element of selecting the “best people.” A Democracy, however, was supposed to be a government of all the people, not just “the best.”

Even in ancient Athens, Democratic rule was controversial. Plato was sceptical. Democratic rule was considered weak because it lay in the hands of ignorant individuals easily swayed by the emotional words of popular agitators. Socrates implied that Democracy was nothing more than mob rule. And Aristotle argued, says the book A History of Political Theory, that “the more democratic a democracy becomes, the more it tends to be governed by a mob, . . . degenerating into tyranny.” Tactical voting, a label invoked whenever the opposition musters support against the favoured candidate, is not a thing of the past.

Other voices have expressed similar misgivings. Jawaharlal Nehru, former prime minister of India, called Democracy good, but then added the qualifying words: “I say this because other systems are worse.” And William Ralph Inge, English prelate and writer, once wrote: “Democracy is a form of government which may be rationally defended, not as being good, but as being less bad than any other.”

Democracy has several weaknesses. First, for it to succeed, individuals must be willing to place the welfare of the majority ahead of their own interests. It seems obvious, but if a candidate for office accepts an election result in his favour, he must logically accept it if the result is not in his favour. This might also mean supporting tax measures or other laws that may be personally disagreeable but necessary for the good of the nation as a whole.

Another weakness was detected by Plato. According to A History of Political Theory, he attacked “the ignorance and incompetence of politicians, which is the special curse of democracies.” Many professional politicians regret the difficulty in finding qualified and talented persons to serve in government. Elected officials may be little more than self-centred political amateurs. And in the era of mass media, a candidate’s good looks or charisma in a televised debate can win him votes that his administrative abilities never would.

Another obvious disadvantage of Democracies is that they are slow-moving. A dictator speaks, and things get done! Progress in a Democracy may be slowed down by endless debates, and powerful political lobbying. Of course, thoroughly discussing controversial issues can have definite advantages. Yet, as Clement Attlee, former prime minister of Britain, once observed: “Democracy means government by discussion but it is only effective if you can stop people talking.”

To what extent the decisions made are truly representative of what “the people” want is debatable. Legislative bodies are composed of individuals directly elected by the people, to represent them and to make laws for the benefit of all. Do representatives vote according to the convictions of the majority of their constituents, or according to their own? Or do they simply rubber-stamp the official policy of their party? Does the role of government ‘whips’ benefit the cause of Democracy, party politics or practical law making?

represent them and to make laws for the benefit of all. Do representatives vote according to the convictions of the majority of their constituents, or according to their own? Or do they simply rubber-stamp the official policy of their party? Does the role of government ‘whips’ benefit the cause of Democracy, party politics or practical law making?

The Democratic principle of having a system of checks and controls to prevent corruption is considered to be a good idea but is scarcely effective. Additionally, many are opposed to further central government regulation. However, loose regulation of financial and banking services is widely cited as a reason for economic meltdown. In 1989 Time magazine spoke of “governmental decay at all levels,” calling a leading Democratic government “a bloated, inefficient, helpless giant.” In Britain, the recent ministerial expenses scandals led to the near collapse of the elected government.

Democratic rule has achieved greater acceptance in this century than ever before. The growing size and influence of the European Union bears this out. Nevertheless, “liberal democracy is now in serious trouble in the world,” wrote journalist James Reston some years ago. Daniel Moynihan warned that “liberal democracy is not an ascendant ideology” and that “democracies seem to disappear.” It seems obvious, but the best of governments cannot outlive the individual representatives, and generally only last a term or two before electoral defeat. Is there ever time to really make significant change, as so often promised?

For these and numerous other reasons, Democracies can hardly be called ideal governments. The obvious truth, as pointed out by John Dryden, 17th-century English poet, is that “the most may err as grossly as the few.” Henry Miller, American writer, was blunt, but nonetheless accurate, when he quipped: “The blind lead the blind. It’s the democratic way.”

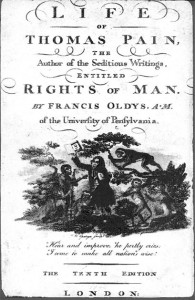

Thomas Paine, vilified in his own time, much admired today, in the seminal Rights of Man (1791), summed up governmental imperfections this way: “Government ought to be a thing always in full maturity. It ought to be so constructed as to be superior to all the accidents to which individual man is subject”. As ‘man dominates man to his injury’, all rule by man will only mirror the errors implicit in man (Eccl 8:9).

the teeming wildlife of sea, shore and countryside. At nightfall, by the glow of a cottage fire, he was entranced by the tales the old folk could tell, as they passed the long winter evenings.

the teeming wildlife of sea, shore and countryside. At nightfall, by the glow of a cottage fire, he was entranced by the tales the old folk could tell, as they passed the long winter evenings.