Today’s teenagers face demands and expectations, as well as opportunities and risks, that are more numerous and complex than only a generation ago. High divorce rates, ambiguous moral guidance, and complex media images all contribute to a lack of stability. Nonetheless, contrary to powerful stereotypes of teenagers as highly stressed, over-assertive, or incompetent, the majority attain adulthood with a positive self-conception and good relationships with both peers and older persons.

However, some teenagers do not have the circumstances, support or opportunities to gain competence and control over their own futures. Before looking at the psychological factors of weight gain or loss, it is essential to consider any physical health factors. To give just two, and there are many, weight gain is an unwelcome side-effect of many types of drugs, and weight loss is often an early sign of malignant disease.

It is now known that more than half the female population of the UK between the ages of 15 and 50 suffer from some form of eating problem, which gives an idea of the scale of the problem, and also, the many individual reasons there are for women to feel dissatisfied with their bodies. It should be noted moreover, that Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia are not solely female-oriented problems; there is an increasing incidence of both in males. There are many causative factors, but without doubt one is what doctors have called ‘the cult of slimness’, the malign side of the fashion industry. Fashion extremes are designed to influence people..

Dr Martin Seligman in Helplessness: On Depression, Development, etc. believed that intrinsic to our development is a need to avoid fear, heightened emotionality and depression induced helplessness. We ordinarily may do so by gaining competence and learning assertiveness, resisting negative, ritualistic compulsions, however, the sociological and other pressure on adolescents is creating the circumstances whereby control can only be achieved in limited, abnormal areas, such as our personal eating and elimination habits. It has to be important for parents to be able to react appropriately to the early onset of the disorder. A wider look at the issue of self-harm and young people, can only lead us to the conclusion our society as a whole has a fundamental problem with true minority empowerment, and teaching appropriate coping strategies for the vulnerable.

Anorexia Nervosa usually develops in young adolescent girls, either during, or shortly after puberty. Some studies suggest 1 in 100 girls suffer from it, and 15 in 100 sufferers dying from it. It is characterised by a substantial self-induced loss of weight, amenorrhoea (irregular periods), and an intense fear of becoming fat, or being perceived as such.

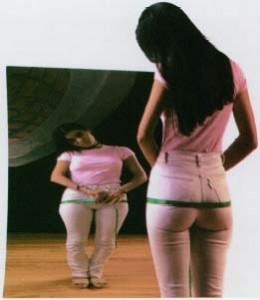

This disturbance of body image is thought by some researchers to be delusional in nature, that is, she may struggle to differentiate between fantasy and reality. Although the disorder may begin in subtle ways, perhaps sensitivity to comments about her shape or weight, perhaps some guilt over newly developing sexuality, perhaps increasing, unwelcome male attention, even, sadly, some ill-advised or forced sexual activity. These factors may be said not to ‘cause’ anorexia, but at a time she feels vulnerable and helpless, dieting may appear a means to regain control.

Anorexia is an illness of denial. She denies herself food, or the pleasure of eating, but also the company of her family or friends, especially if they react negatively to her. She becomes increasingly introspective, and seeks control over her developing body, and any perceived subservience to male attention. She may gain a sense of pride or self-esteem from her ability to deny her body proper nutrition, and so one cannot help but draw a psychological comparison with religious ascetics, past and present, who have claimed by fasting to be the more acceptable to God. This same sense of being special, or even superior, may be a completely new experience for a young girl previously lacking confidence and self-esteem.

She will refuse to accept there is anything wrong, and genuinely find it difficult to see why parents or others are concerned about her weight. “Of course you are not fat,” is meaningless to her. She may begin to enjoy the reaction of strangers who cannot help noticing her emaciated figure; she may choose to wear clothes that accentuate it, although the opposite is sometimes true.

Unlike mature dieters, who often have a very good understanding of balanced nutrition and what constitutes healthy eating, the anorexic girl simply divides foods into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ without consideration of nutritional value, perhaps eating small quantities of processed foods, or low calorie foods like celery, lettuce, or other fruits or vegetables, perhaps with rye bread, although mostly she will appear completely adverse to carbohydrates, as ‘bad’. Although weak and tired, she may force herself to engage in strenuous exercise, often jogging, cycling or swimming.

She may develop a marked sleep disturbance, waking early, between 3a.m. and 5a.m., and unable to get back to sleep. She may dream of eating, and awaken agitated, and feeling out of control. This situation may rapidly worsen, as she seeks to remain awake.

Athletes and Anorexia

Young women involved in sports that place a high value on thinness are three times more likely than others to develop anorexia or bulimia. A 1992 study conducted by the American College of Sports Medicine estimated that as many as 62% of females involved in sports like gymnastics and figure skating struggled with eating disorders. Many well-known athletes have spoken out about their battles with eating disorders, including gymnasts and Olympic gold medal winners Nadia Comaneci and Kathy Rigby. Christy Henrich, who in 1989 was ranked the No.2 gymnast in the United States, died from complications of anorexia in 1994 at the age of 22. The pressure to be thin does not appear to be easing up. The average gymnast in 1976 was 5′3″ tall and weighed 105 pounds; the average gymnast in 1992 was 4′9″ tall and weighed 88 pounds.

Bulimia nervosa

Anorexia is not the only eating disorder, however, nor is it the most prevalent. Bulimia nervosa is a scourge that affects up to three times as many women as anorexia does. Then there is compulsive overeating, which is related to bulimia. Binge eating is also recognized as a stand-alone disorder (BED). Less well known is that many anorexics binge periodically. (See: Binge No More ) The women suffering from bulimia are often older, in their early twenties on. They may appear of normal weight, but be profoundly dissatisfied with their shape or weight. They often experience a distressing sense of disgust with their bodies. They may have intense cravings for certain foods, often rich in fat or carbohydrates, perhaps having abstained from eating that type of food for some time, they may binge on them and then induce vomiting.

They may abuse laxatives, and feel ‘cleansed’ after purging. A cycle of bingeing and vomiting may develop, after a normal meal, or after a vast amount of carbohydrate, for example, cereals, bread, cakes or confectionery.

Is there any underlying predisposition?

Professor Walter Kaye, of the University of Pittsburgh, said brain serotonin activity and mood in young women are known to alter when they binge and purge. Women with bulimia are also known to have an obsession with perfectionism. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps regulate mood. The study found that these alterations and symptoms persisted after recovery from bulimia nervosa, suggesting that they are not merely a consequence of abnormal eating behaviours.

Theoretically, altered serotonin activity could cause anxious and obsessive behaviours, affect the control of appetite and thus contribute to an increased susceptibility to bulimia nervosa (anxiety can be experienced as a troubled feeling, a sense of dread, or fear of the future).

Dr Kaye said: “The development of an eating disorder is often attributed to the effects of our cultural environment, such as the mass media, which places a heavy emphasis on slimness, but while all women are exposed to these cultural factors, only a small percentage develop an eating disorder. Our study may have identified a biological risk factor that plays a part in deciding who develops a disorder.” This research could help scientists to concentrate on developing better treatments, and ways to identify people at risk before the disorder leads to irreversible health damage.

Women who suffer from anorexia and bulimia have described themselves as ‘empty’, having ‘no identity’, or sense of individuality, and not worthy of life’s normal pleasures. This self-apathy, can however, spiral into a self-hatred, and an overwhelming fear they will never feel loved or contented. Loneliness and isolation will only make the eating disorder and her emotional distress worse.

What can be done?

A history of how the problem has developed is very important. The person themselves may not always be able to give the full picture, and the help of family and close friends from the beginning is vital. Because this is such a personal issue, the sufferer is likely to only accept advice or seek support from someone she completely trusts, so professional help may take the form of supporting a third party who is close to her. Please encourage her to speak to her GP, or tell her if you need to on her behalf. As we noted, she will likely have few close friends or family, who may also be part of the problem, and this is more difficult. If it is possible to establish an open, trusting relationship, do so. Remind her isolation leads nowhere. Look with her to find fresh ways to assert herself, new choices that help, not harm her. Keep busy, keep constructive, and remember the thousands who once had an eating disorder, but overcame it, read their stories and learn from them. Never forget there are people out there who want the opportunity to understand and help.

Read more here:

http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/diseases/facts/anorexianervosa.htm

http://www.humanillnesses.com/What Causes Anorexia?, What Can Happen When Someone Has Anorexia?

http://counselingrehab.com/counseling-rehab/an-eating-disorder-treatment-program-can-save-lives/

Reply: Thank you to the people who have responded so far on this Post, And the links I have included above! All the Best, Peter