Rating:

And They Blessed Rebecca: An Account of the Welsh Toll Gate Riots, 1839-1844 (1983) by Pat Molloy

Sometimes with popular heroes, historical or recent, the Robin Hoods or the Che’ Guevaras, hard facts can detract from the legend. An in-depth look at the popular uprisings in Wales a century and a half ago, known as the Rebecca Riots, does not detract from the excitement and genuine feelings of a people who took hope from expressing their disgust at extortion and injustice.

The Rebecca Riots have become a powerful and emotive part of Welsh folklore, conveying through the years the spirit of a long and continuing resistance to English domination and exploitation, for attacks on the toll gates in the dead of night, by men with blackened faces, and disguised as women, were only part of the story. Discontentment in rural Wales ran far deeper than mere annoyance with having to pay the excessive and arbitrary road tolls at legal, and worse, illegally erected gates, and that discontent took many forms.

What was it that distinguished these events from other popular uprisings at the time? Factors include the unexpected passions in a people known for tranquillity, the rapid adoption of the cause across the land, but central to these ideas, who was ‘Rebecca’? Who led the toll gate destructions? In all probability, there were ring leaders, but little co-ordinated planning.

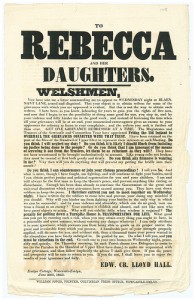

The gangs of small farmers and labourers responsible became known as Merched Beca (Welsh for Rebecca’s Daughters). The origin of their name comes from a verse in Genesis 24:60; ‘And they blessed Rebecca and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them’.

Poor harvests in 1837 and 1838 increased shortages and poverty. There was a good harvest in 1842, but the benefits of this were lost because that was a year of economic depression, so industrial workers could not afford to buy agricultural goods.

Historically there were big social divisions between the gentry (crachach , with a double meaning in Welsh, compare crachen, scab), who owned the land, and the small tenant farmers and labourers who worked on the land. The gentry tended to belong to the Anglican Church and spoke English. They often served as local magistrates or were Poor Law officials or belonged to Turnpike Trusts. Thus they fixed the poor rate, the tolls and the tithes. They had little in common with those who worked on the land and often made decisions that suited their own interests.

The first protests led by “Rebecca” destroyed the toll-gates at Yr Efail Wen, Carmarthenshire, in 1839. Other communities adopted the name and disguise, and other grievances besides the toll gates were aired in the riots. As often is the case, the intrusion of criminal elements, and the venting of personal grudges, was typical of collective rebellion, past or present.

Clergymen of the Church in Wales were targets on several occasions. Perhaps this gives an indication as to how the people regarded them at the time. The Church could demand tithes and other ecclesiastical benefits even though most of the population of Wales were non-conformists. Tithes were payments made for the support of the parish church. These were payments in kind, for example, labour, crops or wool. Other targets were petty local villains such as the fathers of illegitimate children.

Another cause for discontent was the new Poor Law set up in England and Wales in 1834. The rioters attacked workhouses as well as tollgates. The law meant that poor relief (money) was no longer paid to the able-bodied poor. Instead, they were forced to live in a workhouse where conditions were deliberately made harsher than the worst conditions outside (the government believed that the cause of poverty was laziness or a bad character).

In May 1843, the toll gates at Carmarthen were destroyed and in June a crowd of 2,000 tried to burn down the workhouse there. Troops were called in as the movement became more violent. In August, riots took place for the first time in a second major town at Llanelli. The tollgates at Pontardulais and Llangyfelach were also attacked.

The riots caused at least one fatality, in the small village of Hendy, near Pontardulais, in which a young woman, a gate keeper named Sarah Williams died. She had been warned beforehand that the rioters were on their way but refused to leave. On the night of her death she could be heard shouting “I know who you are” by a neighbouring family who had locked their doors from the rioters. She had called for help at the house of John Thomas, a labourer, to extinguish a fire at the toll gate, but when she returned to the toll house, a shot  was heard. Sarah Williams returned to the house of John Thomas, and collapsed and died at the threshold of the house.

was heard. Sarah Williams returned to the house of John Thomas, and collapsed and died at the threshold of the house.

The riots eventually ceased after some of the ringleaders, including John Jones (known locally as Shoni Sguborfawr) and David Davies (Dai’r Cantwr) were convicted and transported to Australia. Jones, unlike Davies, was not convicted of crimes during the riots, but for a later assault charge. The protests prompted several reforms, including a Royal Commission into the question of toll roads.

The Rebecca Riots were a classic example of popular mass protestation against increasing injustices that had been allowed and in some cases, encouraged by the governing classes as a result of the tremendous industrial, economic and social changes of the early nineteenth century, and in addition, circumstances such as the relatively isolated position of West Wales.