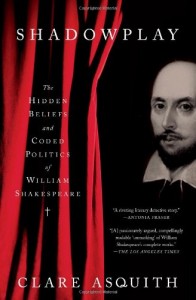

Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare (2006) by Clare Asquith

Rating:

This book is a revelatory new look at how Shakespeare secretly addressed the most profound political issues of his day, and how his plays embody a hidden history of England. In  Elizabethan England many loyal subjects to the crown were asked to make a near impossible choice: to follow the dictates of the State, or their conscience. Four hundred years removed from the English Reformation, it is nearly impossible for us to know what it must have been like for the country to have been ripped asunder and subjects actively persecuted, or even tortured and killed, for their religious beliefs. The era was one of unprecedented authoritarianism: England, it seemed, had become a state dependent on espionage, fearful of threats from abroad and plotters at home. This age of terror was also the era we know as an artistic ‘golden age’ with the greatest creative genius the world had ever known, William Shakespeare. How, then, could such a remarkable man born into such volatile times apparently make no comment about the state of England in his work? He did. But it was hidden. Why? There were sound reasons for not addressing political events directly. Two of his most gifted contemporaries, Kyd and Marlowe did not fare as well. Kyd died after undergoing torture, and Marlowe was almost certainly murdered at the instigation of government.

Elizabethan England many loyal subjects to the crown were asked to make a near impossible choice: to follow the dictates of the State, or their conscience. Four hundred years removed from the English Reformation, it is nearly impossible for us to know what it must have been like for the country to have been ripped asunder and subjects actively persecuted, or even tortured and killed, for their religious beliefs. The era was one of unprecedented authoritarianism: England, it seemed, had become a state dependent on espionage, fearful of threats from abroad and plotters at home. This age of terror was also the era we know as an artistic ‘golden age’ with the greatest creative genius the world had ever known, William Shakespeare. How, then, could such a remarkable man born into such volatile times apparently make no comment about the state of England in his work? He did. But it was hidden. Why? There were sound reasons for not addressing political events directly. Two of his most gifted contemporaries, Kyd and Marlowe did not fare as well. Kyd died after undergoing torture, and Marlowe was almost certainly murdered at the instigation of government.

Revealing Shakespeare’s sophisticated version of a forgotten code developed by 16th-century Catholic dissidents, Clare Asquith shows how Shakespeare was both a genius for all time and utterly a man of his own era, a writer who was supported by dissident Catholic aristocrats, who agonized about the fate of England’s spiritual and political life and who used the popular playhouses to attack and expose a regime which they believed had seized control of the country they loved. Shakespeare’s plays offer an acute insight into the politics and personalities of his era, as well as reflecting the feelings and beliefs of ordinary people. For example Hamlet, interpreted here as a drama of the hesitancy and indecision of the Catholic party in the country, is modelled on Sir Philip Sidney, who was outwardly Protestant but secretly a Catholic sympathiser. Of course there are many candidates for the model of Hamlet; such boldness in identification here simply underlines her own belief in this theory..

Clare Asquith’s research offers answers to several mysteries surrounding Shakespeare’s own life, including most notably why he stopped writing while still at the height of his powers. An utterly compelling combination of literary detection and political revelation, ‘Shadowplay’ is the definitive expose of how Shakespeare lived through and understood the agonies of his time, and what he had to say about them..

The argument that Shakespeare was a secret Catholic dates from at least the 1850’s and was long ridiculed, much as authorship studies continue to be ridiculed today. According to Clare Asquith every time Shakespeare writes “high” and “fair,” he means Catholic; by “low” and “dark,” he means Protestant. A “tempest” refers to the Protestant Reformation, which

Catholics saw as a frightening upheaval in their world. With thousands of English Catholic exiles living on the continent, themes of familial separation and exile in the plays would instantly be recognized. Did Shakespeare employ a ‘Catholic’ vocabulary because he passionately believed it? Again, the author thinks the heroines of The Tempest and The Winter’s Tale, Miranda and Perdita, are “non-sensual” because they are chaste , not realising that chastity, romantic love and womanliness sit easily together – particularly if, as other critics have noted, such heroines reflect at some deep level the feminine power of the Virgin Mary.

Catholics saw as a frightening upheaval in their world. With thousands of English Catholic exiles living on the continent, themes of familial separation and exile in the plays would instantly be recognized. Did Shakespeare employ a ‘Catholic’ vocabulary because he passionately believed it? Again, the author thinks the heroines of The Tempest and The Winter’s Tale, Miranda and Perdita, are “non-sensual” because they are chaste , not realising that chastity, romantic love and womanliness sit easily together – particularly if, as other critics have noted, such heroines reflect at some deep level the feminine power of the Virgin Mary.

Cambridge historian and biographer John Guy has written “Even if only half of Clare Asquith’s argument turns out to be correct she’s written the most visceral, challenging, and compelling book on Shakespeare’s place in history we’ve had for over twenty years.”

“Only in the past few decades have historians revised their assumptions about the period. Far from being a happy time of peaceful transition from Catholicism to Protestantism, the Tudor and Elizabethan eras were in fact the most brutal and turbulent period in English history. Shakespeare required not only the wit to encode his plays and sonnets with historical references, but the confidence that his works would survive until the day their deeper meaning could be clearly understood by posterity. Asquith believes that now, four centuries on, she has finally discovered the key to unlocking their hidden messages. If true — and she makes a convincing argument of her case — then it can only heighten appreciation of the Bard’s manifold gifts. “Clearly,” she says, “he is the cleverest man that ever writ.” It struck Asquith as ridiculous to presume that someone of Shakespeare’s intelligence and curiosity would ignore the momentous events around him. She began to look for clues in his works, alive to the Elizabethan love of wordplay, puns and double meanings. A simple example is a passage that many observers have long believed to contain a typographical error, the line of poetry in Sonnet 23 that goes: “More than that love which more hath more expressed.” On the surface, it does not make sense — until Asquith realized it was a pun. “It should read, ‘More than that love which More hath more expressed,’ ” she says, a reference to Sir Thomas More, the chancellor and Catholic saint beheaded by Henry VIII for refusing to take the oath of supremacy recognizing the monarch and not the pope as head of the Church in England.” (Robert Mason Lee. “Will, the secret rebel.” ‘Macleans’, August 1, 2005).

At every level, Shakespeare’s meanings slip into other meanings and possibilities; it is why the plays can be recreated in different guises by all who encounter them. For critics, too, the man himself mirrors their own natural bias, for Harold Bloom, Shakespeare becomes a humanist gnostic; for Peter Ackroyd he becomes a practical, shrewd, businessman, for David Daniell a Reformatist (Shakespeare and the Protestant Mind (2001) Shakespeare Survey 54); in Clare Asquith’s view he is a fellow Catholic. And thus he succeeds in concealing himself. It seems though, that if he really spent so much time trying to secretly moderate the “powers that be”, it is a shame they didn’t seem to notice; rather akin to our modern-day space broadcasts, if extraterrestrials are out there, they are ignoring us.

man himself mirrors their own natural bias, for Harold Bloom, Shakespeare becomes a humanist gnostic; for Peter Ackroyd he becomes a practical, shrewd, businessman, for David Daniell a Reformatist (Shakespeare and the Protestant Mind (2001) Shakespeare Survey 54); in Clare Asquith’s view he is a fellow Catholic. And thus he succeeds in concealing himself. It seems though, that if he really spent so much time trying to secretly moderate the “powers that be”, it is a shame they didn’t seem to notice; rather akin to our modern-day space broadcasts, if extraterrestrials are out there, they are ignoring us.

In summary, Clare Asquith’s theory is a fascinating, revealing look at the familiar plays in an unfamiliar context, the world of English recusant Catholicism. Reading Shakespeare as allegory in no way diminishes an equally valid literal understanding. I cannot personally accept the theory answers as many questions as it claims, although I do accept the validity of asking the questions themselves. I believe a lot more work is needed to prove the case, and in particular reconcile it if possible with the theory Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, was the author behind the works of Shakespeare. There is less conflict here than might appear. I assume she writes as a Stratfordian (accepting the traditional identity of William Shakespeare of Stratford on Avon) or possibly this is because she views her conclusions radical enough. The strength of the book for me is the detailed look at the individual plays. She makes comprehensible some of the stranger twists and turns in their plots. I can recommend it for her analysis of the plays alone, and I broadly accept the central premise of the hidden code. Certainly reading the plays after Asquith is a new experience.