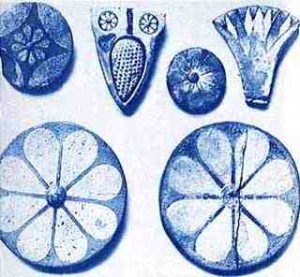

Eight-petaled rosettes similar to those on the Phaistos Disk and on various ancient game-boards, such as discovered at Ur in Mesopotamia, and the example shown here from Knossos, Crete, appeared also on many other objects, over a wide geographical area and span of time. They appear to be solar symbols, or more precisely represent the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and so indicated the passages from one state of existence into another.

In Mesopotamia, the eight-leaf rosette was also the emblem of the fertility goddess Ishtar and her associated planet Venus. However, this apparent broadening of the symbol only confirms the basic meaning of birth, death and rebirth.

In a well-known myth, Ishtar descended into the underworld and was held there as if dead, before she returned to life, just as Venus the evening star disappears from the sky for some time and then heralds as the morning star the return of the life-giving light. The symbolism is the same as that derived from the cycles of the sun.

Heavenly matches for the eight leaves

Venus and the sun also both match the eight leaves of the rosette with aspects of their observable behaviours. Venus disappears for an average of eight days in the glare of the sun during its transition from evening to morning star. Furthermore, five complete Venus cycles of 583.92 days each come close to eight solar years of 365.2422-days each, and they match them exactly, at 2920 days, when both periods are rounded to whole numbers.

Eight solar years are also the time it takes the “new” midwinter solstice sun to come again close to a new moon, within a day and a half of 99 months at 29.5306 days each. Here again, the rounded numbers come even closer, to 2920½ days, if the fractional day of the lunar month is counted simply as half a day.

The eight years from one such “meeting of sun and moon” to the next were called a “Great Year” and measured the life span of the sun because at each of these “meetings”, the old sun died and the new one was born for the next cycle. World cycles based on the renewal of celestial conjunctions preoccupied the early sky watchers, and have received attention in recent books by authors such as Adrian Gilbert and Maurice Cotterell.

In many Bronze Age religious cultures, the sun was identified with the king, and so this “Great Year” determined also the length of royal reigns, at least theoretically. When it ended, the old king was to die to be replaced by another one. Much has been written about this ancient belief since the 1920s when Sir James George Frazer built his monumental “The Golden Bough” around the idea that the kings were actually killed on those occasions.

belief since the 1920s when Sir James George Frazer built his monumental “The Golden Bough” around the idea that the kings were actually killed on those occasions.

Meanwhile, serious doubts have arisen about whether the executions were literal, but be that as it may, periodic renewal, or coronation rites for kings are well attested from many ancient civilizations, and each such renewal had to be preceded by a death. Whether that death was real or symbolic makes no difference in this context.

The rosette/flower/star has been linked by H.S. Smith to the concept of ‘divine’ kingship and to the Sumerian and especially Elamite symbolism. It is believed the rosette was a symbol for kingly authority, or possibly the king’s power of life or death over subject peoples.

The mythological king Minos of Crete was said to reign for eight years and to then visit the cave of his father Zeus every ninth year to bring back a new set of laws. Entering a cave appears to be a symbolic substitute for entering the underworld of death, and this particular cave was the burial place of the Cretan Zeus who did not share the immortality of his mainland counterpart, but died like the Egyptian Osiris. The new laws Minos obtained in this abode of death from his dead father signified the renewal of his reign.

The expression “every ninth year” actually means “at the end of every eighth year” because the ancient Greeks and many of their Near Eastern neighbors used the inclusive way of counting time. In this system, pregnancies lasted ten months instead of the modern nine, as stated in the Apocryphal Wisdom of Solomon 7:2.

The interval between Minos’ journeys through symbolic death to renewal matched therefore the eight-year cycle of the sun.

The number eight may also be a symbol of new beginning in the Bible, as when Noah saved eight persons from the great flood.

Similarly, the Jewish rite of circumcision is performed on the eighth day, and in Leviticus 9:1, the inauguration of the Tabernacle as the new dwelling place for the presence of God took place after seven days of preparation on the eighth.

Eight kept that meaning in later ‘christian’ iconography. The star of Bethlehem was usually shown with eight rays. Also, in another survival of inclusive counting, Easter Sunday, when Christ rose from the dead, was seen as the eighth day after Palm Sunday, the day on which Jesus entered Jerusalem.

Ancient examples of the eight-leaf rosette

The rosette with eight leaves occurs on many ancient game-boards, as illustrated.

The symbolist Manfred Lurker proposed in his illustrated Dictionary “Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt” that the rosette represented the sun breaking forth after the night and the defeat of the abysmal darkness.

The rosette or ray motifs on Egyptian seched-circlets prefigure similar motifs painted behind Christ and the saints in more recent religious art. The cross motif was used by Chaldeans, Egyptians and others.

The Bronze Age Cretans, too, decorated many objects with eight-leaved rosettes, including the ceiling of the “Throne Room” in the palace at Knossos. Like the later Philistines and Canaanites, they used that rosette as one of their favorite pottery symbols.

The presence of golden eight-leaf rosettes in tombs at Mochlos, Crete, from around 2,000 BCE, and in Mycenaean graves from more than half a millennium later, attests that in these cultures, too, this sign was associated with a symbolism of death to be followed by rebirth.

Some of the wigs on the human-shaped clay coffins from Philistine-occupied Beth-Shean bear lotus flowers, and the sarcophagus of king Ahiram from the Phoenician city of Byblos, dated to about the time of Solomon, displays a ceremonial scene common in Phoenician art which shows him holding a lotus flower as a sign of his rebirth and apotheosis.

The Classical Greeks were equally fond of the eight-leaved rosette motif. One particularly revealing stone sculpture at the former site of the Eleusinian mystery cult shows an initiate emerging from the center of a giant eight-petaled flower bud that is marked all over with eight-leaf rosettes. The context leaves here no doubt that this sculpture illustrated the spiritual rebirth which the initiate to those mysteries was said to achieve. Since the rose was sacred to Aphrodite, the church later used the rose as a symbol for Mary.

In the sun cults of ancient Northern Europe, a wheel with eight spokes represented the sun and its regenerative powers but appeared also as a symbol of death and destruction. The Celtic wheel-cross is undoubtedly linked to the rosette symbol, as depicted in the Gospel of St Chad.

Similarly, the symbolic meaning of the Near Eastern rosette included death, as on a fragment from the throne of pharaoh Thutmosis IV where that sign marks an enemy crushed by the king’s foot.

On Greek vase paintings of battles, or of Theseus killing the Minotaur, an eight-leaf rosette often conveyed that the combat ended in death. For instance, a vase painting from about 660 BCE shows a clash between the warriors on two ships. Where their spears meet over the opposing bows, the ancient painter placed the eight-leaf rosette to symbolize death.

In Minotaur-slaying scenes, the rosette marks sometimes that monster to announce its upcoming death. At other times, it decorates Theseus and can be seen as a sign that he will return from his excursion into the labyrinth, a symbol of the underworld, and will thereby be regenerated.

In India, and in a few cases also in ancient Mesopotamia, an eight- leaf rosette adorned the memorial stelae of widow- burning victims who had been killed in their husbands’ funeral pyres.

In summary, the contexts in which we find the eight-leaf rosette suggest that it represented the birth, death, and rebirth of the sun (and/or of the planet Venus), in many of the ancient Near Eastern religions. The motif survived the centuries, and spread throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, in a context suggesting it retained its original symbolism, and was not simply decorative.

References

Atlas of the Greek World (1980) by Peter Levi

Virtual Archaeology(1997) by Maurizio Forte and Alberto Siliotti

Art of the Ancient Near East (1961) by Seton Lloyd

Greek Art (1973) by John Boardman

Peoples of the Sea (1977) by Immanuel Velikovsky

Art in Wales: An Illustrated History (1978) by Eric Rowan