Madeleine Bunting (2005) Rating:

“Some people take, and some people get took. Only they know they’re getting took and (they think) there’s nothing they can do about it..” Fran (Shirley Maclaine) to CC Baxter (Jack Lemmon) in Billy Wilder’s ‘The Apartment’ (1960).

“Some people take, and some people get took. Only they know they’re getting took and (they think) there’s nothing they can do about it..” Fran (Shirley Maclaine) to CC Baxter (Jack Lemmon) in Billy Wilder’s ‘The Apartment’ (1960).

“In the ancient world individuals were often enslaved without choice, but some sold themselves as slaves in order to eat…and so in society.” C S Lewis (1958)

This is a contemporary account of the attack on the loss of liberty suffered by ordinary working people. Since the 18th Century, demands imposed by landowners, the industrial revolution and employers, in both the public and private sectors, have grown in intensity.

Some of the thinkers of the 18th Century believed that commerce, machinery and wages would bring freedom to the British peasantry. But that was not how William Blake, William Cobbett, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Hardy and DH Lawrence, among many others, saw it. They saw capitalism and its machines as slave drivers. The class system, with a new recognition for a middle class of traders and employers, was only redefined by industrialization.

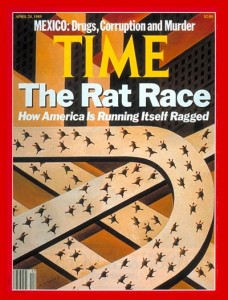

Fast-forward to the present, what happened to the promise of work? Hard work was supposed to bring wealth and satisfaction. Instead, for many, it has brought worry, illness, poverty and debt. Why in Britain do so many of us voluntarily submit ourselves to stagnant wages, job insecurity, stress and exhaustion ? Why do we willingly enslave ourselves? These are the questions addressed here.

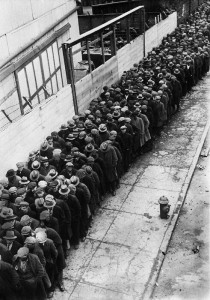

From the late 18th and 19th centuries, the unwritten history of industrialization was to take a nation of strong-willed and independent agricultural workers and transform them into docile wage slaves. Off the land and in the factories. The two principal methods used by ‘the powers that be’ were fear of God and fear of hunger. A new work ethic was promoted by the clergy, who preached every Sunday to the new working class that it was their moral duty to work hard. Who benefits most by the ‘Protestant work-ethic’? Crucially, wages were set low to ensure the worker returned to work on Monday morning. Hunger was found to be an effective prod to ensure that workers – men, women and children from the age of six upwards were all wage earners, to the detriment of home and family.

Surely things are better in Britain today? The physically brutal conditions have gone, and no one is so poor today that they starve. We may not die from hunger, but we are certainly overworked and stressed out. Historically, the trade-off for workers meant exchanging freedom for security, ‘jobs for life’. With the so-called ‘epidemic’ of zero-hours contracts the death-knell has sounded for job security. The physical hardships of working in the old mills have been replaced by new psychological hardships. Wages are low, hours are long and stress levels are rising. Women may be liberated, but in many cases, working full-time whilst caring for a family.

One coercive technique used today is the concept of brand loyalty and

“teamwork” to give the illusion that the company is bringing some sort of meaning into people’s lives; meaning that was once provided by church and community. Thus they hope to inspire their staff. Brands cleverly use inspirational slogans to convince their employees they are on some sort of mission and not merely under-paid and exploited profit-creators for a handful of anonymous fat-cats. I loved the story of company sales figures regularly pasted up on the back of the staff toilet doors, tempting to think how they might be used… Words such as “passion” and “commitment” are bandied around. In this book, Asda, for example, encourages its employees to believe they are lucky to be part of a caring family. Managers look for cheerful souls, team players. And woe-betide anyone who doesn’t feel like joining in.

The other factor that gets us to work in the morning, argues the book, is consumer desire. This is the replacement for the old hunger fear. There are millions of products out there competing for our money, some good value, most not. We know the companies play on our natural desire for freedom to promote their products. These days, our freedom can consist of little more than deciding between Morrisons and Tesco’s, eating in or going out, lager or beer, butter or margarine.

The government has also chosen to support large companies, British or foreign, by promoting the work ethic in policy and propaganda. What about that ‘opt-out’ from European Working time Regulations? Also working tax and child tax credit, for example, in effect subsidises employers who pay low wages. According to Citizens UK, which organises community campaigns, most of those earning less than the living wage are employed in the retail sector. The charity said this meant most supermarket staff needed in-work benefits – which it argued meant taxpayers were “subsidising private companies by almost £11bn per annum“.

The message, it appears, is that any job, however meaningless, is better than no job. This comes as no surprise when whoever wins an election will promise work for all. In addition, Government obsession with “targets” has led to an epidemic of over-work, fudged results and corruption, as time-pressed public servants struggle to meet absurd demands.

For all the talk about “work-life balance” and “family values”, the government remains firmly attached to work as a panacea for all social ills. As Tony Blair said in 1998, “Anyone of working age who can work should work,” and included single mums, the long-term sick and the disabled. That’s why companies are required by law to employ a percentage of the disabled, there literally isn’t enough of them to go round.

Work experience has it’s benefits, but one 20 year old autistic man in a well-known supermarket, having built a six foot high banana ‘pyramid,’ couldn’t cope with the shoppers disturbing his creation. I thought his response was pretty reasonable, a bit like taking a nap in Tracey Emin’s bed.

So if it is true that work as we experience it is a gigantic confidence trick, the question remains: if we could imagine a fear-free life without mind-numbing work, then what do we replace it with? How do we want to live?

One danger has to be conformity. Every worker is expected to be the same as the next, even companies themselves offer much the same in terms of working conditions, everything merges into one. As an antidote, John Stuart Mill advocated eccentricity, “Precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach, it is desirable, in order to break through that tyranny, that people should be eccentric. Eccentricity has always abounded when and where strength of character has abounded; and the amount of eccentricity in a society has generally been proportional to the amount of genius, mental vigour, and moral courage which it contained. That so few now dare to be eccentric, marks the chief danger of the time” (On Liberty, 1856).

Let’s face it, the overwork culture feeds off collective inertia, fatigue and failure of imagination. It is an emotional dead-end. A new fear for today: Fear that you might not be good enough, unique enough, productive enough or creative enough to catch the attention or approval of your boss. You can do without feeling like that every workday.

Another answer maybe is to live well on less. Many interviewed in the book felt powerless in the face of demands for more work. If we did not desire the panoply of products that are sold to us each day, then we will not have such a voracious appetite for money, with so many viewing over-time as a necessary part of their wage. Less money means less work. Less work means more freedom to do our own work or do what we want to do. One message is that money in the form of a big salary, is not all-important to most people, or they would never put up with so much in the workplace. The book gives a few inspiring examples of families who have downsized, gone part-time or self-employed.

Could the Government be doing more? Are there legislative solutions – more generous maternity and paternity leave, and so forth? More bank holidays? But first, perhaps, we need to ”identify true freedom from the many fake versions available…take responsibility for using freedom with wisdom and insight…meet human needs rather than exploit human fears and vulnerabilities.” A wisdom ethic to master the work-ethic.