which, considering he claims many of the original locations of ancient Greece, Egypt, and Palestine in Britain, is something of an understatement.

which, considering he claims many of the original locations of ancient Greece, Egypt, and Palestine in Britain, is something of an understatement.

which, considering he claims many of the original locations of ancient Greece, Egypt, and Palestine in Britain, is something of an understatement.

which, considering he claims many of the original locations of ancient Greece, Egypt, and Palestine in Britain, is something of an understatement.Rating:

Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis

Freud, according to this 1995 book, dispensed psychoanalysis “as if it was a science, when it seems more akin to a faith or a cult, with Freud as a modern ‘Messiah'”. It is an explanation of the human condition firmly rooted in Darwinian evolutionary theories. That Freud was able to do so may well be down to the 20th century spiritual vacuum, the failure of the churches post world war, and their little, if any, moral authority. It is in this respect that Freudian psychoanalysis bears comparison with Darwinian evolution. Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical theory remains a popular psychiatric approach. Its use, however, has been chiefly in the United States. Thus New York, with nine million inhabitants (1980) had almost a thousand psychoanalysts, whereas Tokyo, with eleven million people, had but three!

What similarity is there between two species of birds, very different in many ways? They both cause major difficulties for evolutionists, and in their behaviour, exhibit forms of symbiosis that confound Darwinian natural selection. No explanation they offer has convinced me, look at the facts for yourself.

The Huia The Huia belonged to a family found only in New Zealand, a family so ancient that no relation is found elsewhere. Only the Moa and the Kiwi are likely to be older . Before the arrival of Europeans it was already a rare bird, confined to the mountain ranges in the south east of the North Island.

. Before the arrival of Europeans it was already a rare bird, confined to the mountain ranges in the south east of the North Island.

The Huia was a bird of deep metallic, bluish-black plumage with a greenish iridescence on the upper surface, especially about the head. The tail feathers were striking in having a broad white band across tips.

At the base of the bill, on either side of the mouth hung the fleshy wattles characteristic of the family Callaeidae, which were bright orange in the Huia. In both sexes the bill colour was ivory white and the legs were bluish grey. In size the Huia were slightly larger than the introduced Australian magpie.

But the most remarkable feature of the species was the marked difference in size and shape of the bill and this difference was so extreme to cause early ornithologists, such as the renowned John Gould, to think that the male and female belonged to different species.

Born around the year 1320, near old Richmond, Yorkshire, John Wycliffe was sent to Oxford University, where he rose to become master of Balliol College by 1361 and, some years later, a doctor of theology. His expertise with English law and Canon law was not merely the result of his interest in the subject, but of a deep-rooted desire to see English liberties defended and maintained. From the time of King John a tribute had been paid to the Pope in acknowledgment of his supremacy. In 1365 a demand was received from Pope Urban V for this money, along with arrears covering more than 30 years. The next year, Parliament decided that King John in unilaterally agreeing to the tribute, acted beyond his right, that the feudal tribute would be resisted. Seeing their determination, the pope dropped his demand, but not without generating some controversy on the part of the members of the monastic orders in England.

In reply, Wycliffe wrote a tract in which he legally defended the stand Parliament had taken. His argument was couched in the words of various Lords in Council: “It is the duty of the Pope to be a prominent follower of Christ; but Christ refused to be a possessor of worldly dominion. The Pope, therefore, is bound to make the same refusal. As, therefore, we should hold the Pope to the observance of his holy duty, it follows that it is incumbent upon us to withstand him in his present demand.”(John Wycliffe and His English Precursors)

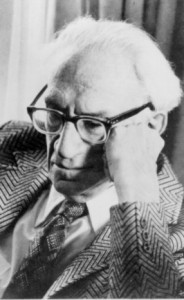

Immanuel Velikovsky, born in Vitebsk, Russia, 10 June 1895. He learned several languages as a child, graduating with full honours from Medvednikov Gymnasium, Moscow. He later studied at Montpelier, France, and Edinburgh, Scotland. At the outbreak of World War I, he returned to Moscow studying law and ancient history. He received his medical degree from Moscow University in 1921. In 1923, he married Elisheva Kramer, an accomplished violinist from Hamburg. That year they moved to Palestine, and he began medical practice. After studying in Vienna under Bleuler, a pupil of Freud’s, he began practising Psychoanalysis. In 1930, Velikovsky was the first to suggest that encephalograms would be found that would characterise epilepsy. In the summer of 1939, Velikovsky came to America to further his researches. He was one of the greatest original thinkers of the twentieth century, and his legacy continues to be the boldest, most provocative theory on the history of this earth, physical and cultural, a theory that has and will only increase in significance as time passes. If not correct in every detail, many of his ideas pass for the original work of others. “During the course of his life, Velikovsky suffered the loss of his homeland, and the family left behind as he was forced to flee Bolshevik Russia, the near extermination of his race at the hands of the Nazis, the attempted suppression of his life’s work, and savage attacks upon his character and scholarship throughout the last three decades of his life”. As he once said, ” A newly discovered truth is first attacked as being false; but when it is finally accepted as true it is attacked as not being new.” Continue reading Immanuel Velikovsky 1895-1979

Immanuel Velikovsky, born in Vitebsk, Russia, 10 June 1895. He learned several languages as a child, graduating with full honours from Medvednikov Gymnasium, Moscow. He later studied at Montpelier, France, and Edinburgh, Scotland. At the outbreak of World War I, he returned to Moscow studying law and ancient history. He received his medical degree from Moscow University in 1921. In 1923, he married Elisheva Kramer, an accomplished violinist from Hamburg. That year they moved to Palestine, and he began medical practice. After studying in Vienna under Bleuler, a pupil of Freud’s, he began practising Psychoanalysis. In 1930, Velikovsky was the first to suggest that encephalograms would be found that would characterise epilepsy. In the summer of 1939, Velikovsky came to America to further his researches. He was one of the greatest original thinkers of the twentieth century, and his legacy continues to be the boldest, most provocative theory on the history of this earth, physical and cultural, a theory that has and will only increase in significance as time passes. If not correct in every detail, many of his ideas pass for the original work of others. “During the course of his life, Velikovsky suffered the loss of his homeland, and the family left behind as he was forced to flee Bolshevik Russia, the near extermination of his race at the hands of the Nazis, the attempted suppression of his life’s work, and savage attacks upon his character and scholarship throughout the last three decades of his life”. As he once said, ” A newly discovered truth is first attacked as being false; but when it is finally accepted as true it is attacked as not being new.” Continue reading Immanuel Velikovsky 1895-1979

How important is curiosity? When considered, it is a vital part of what makes us human. With age, we often lose the sense of wonder confronting us in our world, so how can we cultivate our interest in our own surroundings, however mundane?

How important is curiosity? When considered, it is a vital part of what makes us human. With age, we often lose the sense of wonder confronting us in our world, so how can we cultivate our interest in our own surroundings, however mundane?

Prepare to be amazed by something every day. Be open to the possibilities around you. Break the routine of your activities. Cycle or walk to work. Take a bus for a change. Stop to chat to people. Ask something you might not feel confident about normally. Try something different on the café menu.

Buy a notepad you can write down your ideas as they occur to you, or simply use it to doodle on while you wait. Most creative people keep a record of their thoughts, experience should tell us all how much we lose by not doing so. After a day or two, read over your ideas and reflect on them. You may find a pattern emerging that indicates your creative response to your environment. Try the suggestions in : The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

Learn to use the Internet effectively. For most, if not all, casual users, it can appear daunting; how do you decide from half a million search responses which is the one you want? What if you miss a better one? Creative people cut through those worries, and learn the effective ways to use what they find, they can organise information so they can find it again, and they don’t overload their own memories whilst using a machine designed to do the same task more efficiently. Flow diagrams are good; in similar fashion we display a family tree, with the possibility of adding information in ‘layers’, using spread-sheet software, for example.

Rating:

The Cruel Peace: Everyday Life and the Cold War (1992) by Fred Ingliss

As one of the generation that grew up with the Cold War, what did it mean at the time? I now realise it was very much a third-hand experience, a vague, somewhat indeterminate, threatening presence that although seemingly far removed from teenage life, threatened to obliterate all. It was conveyed through television, above all, on the news, documentaries and films, but also newspapers and books.

`On the Beach’ by Nevil Shute, I remember reading as a 12 year old, a profoundly depressing story of the end of the world `not in a bang, but a whimper’. Later, `The Third World War’ by General Sir John Hackett, which pretty convincingly said that the so-called `nuclear peace’ since 1945, was a cover-up. Perhaps that was why I failed to feel enthusiasm when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, although it would be churlish to ignore the changes for the better in Eastern Europe.

Continue reading The Cruel Peace: Everyday life and the Cold War

Rating:

“Hamlet” (York Notes Advanced)

“Hamlet” (York Notes Advanced)

“Whether Hamlet is ever mad, or considered mad, is argued over by critics long and hard. No two performances will convey the same impression of the state of Hamlet’s mind after his interview with the Ghost” (York notes,p86). Every critic, of course, has a different opinion. The majority appear to concur he went mad, with most favouring the position he intended to feign madness in order to exact revenge for his father’s death, perhaps without foresight as to the precise means, but rapidly succumbed to genuine madness as events unfolded. It is unclear what level of insight he had at each stage of the tragic process.

Rating:

The Thirteenth Tribe: The Khazar Empire and Its Heritage (1976) by Arthur Koestler

In this book Arthur Koestler traces the history of the ancient Khazar people, who from around 750 AD, converted to Judaism. They lived in the Caucasian region, modern-day Ukraine, and were related to other Turkish tribes, the Magyars, Huns, and Oghuz. Were they wiped out in the Middle Ages by the Mongol hordes of Gengis Khan sweeping westward at around 1222 AD? There is substantial evidence that the survivors migrated north and west, primarily to Hungary and Poland.

In this book Arthur Koestler traces the history of the ancient Khazar people, who from around 750 AD, converted to Judaism. They lived in the Caucasian region, modern-day Ukraine, and were related to other Turkish tribes, the Magyars, Huns, and Oghuz. Were they wiped out in the Middle Ages by the Mongol hordes of Gengis Khan sweeping westward at around 1222 AD? There is substantial evidence that the survivors migrated north and west, primarily to Hungary and Poland.

Continue reading The Thirteenth Tribe: The Khazar Empire and Its Heritage

Rating:

Real Lace by Stephen Birmingham

Published in 1973, this book is getting on a bit, however, as a thoughtful social history of some fascinating families, it deserves to be better known. The generation that emigrated from starving Ireland in the 1800’s often arrived in America alone and penniless, facing slums, more poverty, prejudice and disillusionment, but at least spoke English.

Published in 1973, this book is getting on a bit, however, as a thoughtful social history of some fascinating families, it deserves to be better known. The generation that emigrated from starving Ireland in the 1800’s often arrived in America alone and penniless, facing slums, more poverty, prejudice and disillusionment, but at least spoke English.