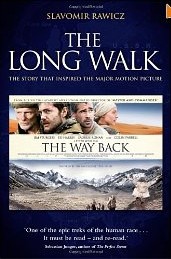

The Long Walk: The True Story of a Trek to Freedom (1956) by Slavomir Rawicz

Rating:

The Long Walk, first published in 1956, is a gripping account of a Polish officer’s imprisonment in the Soviet gulag in 1940, his escape and then a trek of 4,000 miles (6,437km) from Siberia to India, surviving unimaginable hardships along the way, testing the seven men and their companion, a seventeen year old girl they came across on the way, to the limits. Its dramatic passages tell of extremes of exhaustion, starvation and thirst as they survived snowdrifts and storms and even the pitiless Gobi Desert.

“In the shadow of death we grew closer together than ever before. No man would admit to despair. No man spoke of fear. The only thought spoken out again and again was that there must be water soon. All our hope was in this.”

Australian director Peter Weir, celebrated for contemporary classics such as ‘Dead Poets Society’ and ‘The Truman Show’, decided the account deserved filming. “As a feat of endurance and courage and the tenacity of human beings to survive, I thought it was superb. I asked, ‘Does it stay with you enough to want to pursue it as a film?’ And this was the case.” The film, inspired by the book, but not a straight re-telling, was released December 2010 as ‘The Way Back’.

The subtitle of the book is ‘The true story of a trek to freedom’ but there is a controversy over this. There was evidence that suggested that Rawicz had not told the truth about his past, and that although he had been a prisoner in the gulag, he never escaped, but was released under an amnesty in 1942, and the documents, discovered by an American researcher, Linda Willis, in Polish and Russian archives, also show that rather than being imprisoned on a charge of espionage as he claimed, Rawicz was actually sent to the gulag for killing an officer with the NKVD, the forerunner of the Soviet secret police, the KGB. This could of course, be a fabrication.

Peter Weir researched the controversy. “It was enough for me to say that three men had come out of the Himalayas, and that’s how I dedicate my film, to these unknown survivors. And then I proceed with essentially a fictional film.”