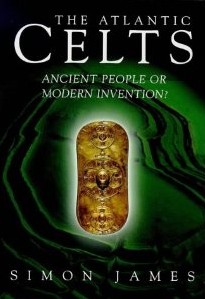

The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention? (1999) by Simon James

Rating:

The theory presented by Simon James in The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention? is that the pre-Roman inhabitants of the British Isles were not a single people united by language and culture, that had invaded, destroyed or assimilated earlier unrelated peoples, nor indeed were they ethnically related to the Celts in mainland Europe. Discoveries in Britain of ‘La Tene’ style artifacts prove only the existence of trading links or raids to and from Europe.

people united by language and culture, that had invaded, destroyed or assimilated earlier unrelated peoples, nor indeed were they ethnically related to the Celts in mainland Europe. Discoveries in Britain of ‘La Tene’ style artifacts prove only the existence of trading links or raids to and from Europe.

The term ‘Celt’ was used by the Greeks and Romans as a designation for some of their barbarian neighbours to the north. ‘Celt’ as applied to the Scots, Welsh and Irish was not used before the eighteenth century, and appears to be an explanation entirely dependent on similarities in language. The term was quickly developed by other scholars to describe cultural or national identities.

In his 1707 work Archaeologia Britannica , Oxford scholar Edward Lhuyd proposed that similarities in the Welsh, Breton, Cornish, Irish, and Scots Gaelic languages were attributable to a common European origin. In that same year, the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland created a new political identity: ‘British’. The same political pressures sought the assimilation of Ireland through the Act of 1800. The confusion, however, may have originated with Julius Caesar. He identified three major tribes within Gaul (France) prior to the attempted invasion of Britain, “Gaul comprises three areas, inhabited respectively by the Belgae, the Aquitaini, and a people who call themselves Celts, though we call them Gauls. All of these have different languages, customs and laws.” The idea that people living out on the islands of the Atlantic fringe might call themselves ‘Celts’ came much later – and in effect involved the adoption of an imaginary ancestry and heritage. The Britons, who according to the Welsh triads, called themselves Khymry, were not Gauls, never called themselves ‘Celts’ but may have been closer related to the Belgae or Aquitani..